What do you do in your free time? We ask this harmless question to better know a person by their interests or when we want to steer the conversation away from work. I pose it when I sense that people aren’t inspired in their career, because of the way they say things like, “It’s just a job”, with the same tone of resignation one might use in the phrase, “But I can control it with medication”. Free time is a strange concept, because it implies that the rest of our time is not free; we pay for it with our labor. It is only the small remainder of spare time that we can call our own; the leftovers from the banquet of life.

I frequently hear people talk dismissively about their jobs, especially the higher up they are in the corporate pyramid. One of my workshop participants was a senior VP for Proctor & Gamble. When I asked him what he did, he began with, “I’m the Regional Director of Sales…”, then he paused, chuckled to himself and said, “I sell toothpaste.” What came next was how much he loved horses but had no opportunity to ride, how much he missed Virgina and how we all make sacrifices. It made me want to cry.

In my corporate work-life balance courses, I use a nice analogy from my friend Dana Breitenstein to introduce the western view on time. We conceive life as something divided up like the segments of an orange. We have our work life, spiritual life, family life, private life, physical life, educational life and so on. All of these are separate and compartmentalized as we don’t want one to interfere with the other. This creates internal disagreement; a disharmony that amounts to a kind of schitzophrenia. It fills us with contradictions.

It’s the competitive ambitious persona at work, who struggles to reconcile with the easy-going and compromising care giver. The personal self who can’t live up to the promises or expectations of the spiritual self. The private part of us who despises the superficial, inauthentic social self. When we talk about self loathing, we should be specific about which self is loathing which.

Another way in which we pit ourselves against ourselves is to try and assign time to everything and therefore “balance” our life. Work-life balance is a contradiction. It is a kind of perverse corporate-speak, and because I have learned this language, I use it to sell my own ideas, which I believe better resolve this incongruity. To presume that there is a separateness between life and work is like saying “I love my family but I hate my kids.”

So consider that the majority of stress in our life comes not from work, but from trying to balance “work” with “life”. Because we treat work as an obligation and something that robs us of our free time, we resist its demands. Our work is not only part of our life it is our life. It’s where we learn to get much of our status and validation and forms the hierarchy of how we relate to people. When we just tolerate work and seek to live a wonderful life, we’re creating a contradiction that we cannot ever hope to reconcile. If we want to remove the stress between work and life, we must learn to become comfortable with ambiguity, and integrate rather than try to maintain separateness of selves.

I have devoted a significant part of my life to deliberately blurring the lines between conventional definitions of work, play, family, hobby, learning, worship and rest. I do this because there is a huge amount of psychic energy that can be liberated from holding up all the partitions between states. I found that when I began to treat work as a learning game, I could create endless variations of this game that other people would pay to play. Mowing the grass? This is a kind of meditation for me, and there’s no way I would pay someone to do this when I’m home, because it fills me with a sense of pride and serenity. I come from the midwest, where I was raised in the religion of lawn care. It’s not a task to be outsourced, it’s a ritual wherein I commune with nature. Household chores? Beautifying my living space, actually.

What some may call “positive thinking”, I consider to be an entirely different paradigm of what constitutes obligation. I believe we turn choices into obligations in order to reduce the anxiety that comes from making choices. This anxiety is our paradoxical relationship to freedom, where we justify the necessity of doing something we don’t want to do by defining it as obligation. Paying taxes, standing in line at the DMV, sitting through a fun-sucking meeting, are somehow more tolerable when we tell ourselves, “This is how it is.” What we choose to ignore is the payoff we get from them.

When I treat all my time as free time, I notice how enjoyable they can be. Everyday errands become an adventure. I strike up a conversation with a 5-year old while in line at the bakery and am schooled in the merits of the Crayola glow station. While at the garage to pick up a replacement cup holder, I learn from my mechanic, Michael, how changing my fuel filter will significantly improve gas mileage on the Rover and I learn how to repair a broken bicycle chain while at the shop to change a punctured tire. What began as a list of “have to’s” unfolded as an enjoyable learning experience.

I remember 15 years ago, when my friend Andrew Henderson, a U.S. Navy JAG was visiting Hong Kong with his ship’s battle group, I came down from Guangzhou, China, where I was living, to meet him. While enjoying a VIP tour of the aircraft carrier John Stennis, Andy said how great it was that we, college classmates were meeting in Hong Kong. I said that I had to come down to Hong Kong at least once a month to meet clients and do my banking. “That’s so cool,” said Andy, “That you get to visit Hong Kong so often.” At which point it dawned on me that yes, “I get to come to Hong Kong”, not “I have to come to Hong Kong.” Previously, I had seen this 5-hour round-trip journey as a huge hassle; taxis, trains, border crossings, crowded subways, and a long line at HSBC. In that moment, it changed from an obligation to a privilege, and I began to enjoy it. More amazingly, people now went out of their way to be kind to me. Girls smiled at me, food tasted better and service in general seemed to magically improve. What was an errand that I dreaded, became something to look forward to.

The things we have to do are joyless. The things we get to do are awesome. These are often the same things.

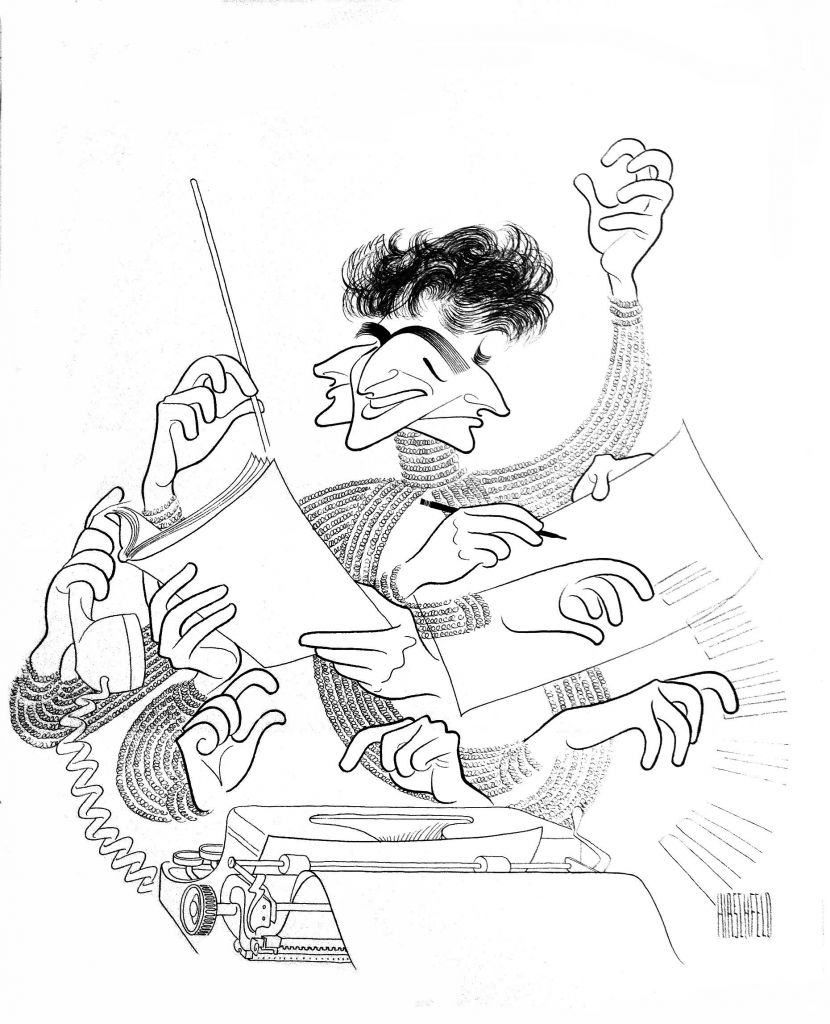

Like the Hindu god Shiva, who dances the world in and out of existence, we are a continuous convergence of opposing forces that we should embrace, not partition or resist. When we celebrate our paradoxical natures, forgiving the differences between doctrine and practice, between intention and action, we are free to relate to our world as we choose, instead of how we have to. What we will find is passion; a fire that consumes and renews with a creative power that once we may have feared but learn to welcome.